Modigliani: “I am neither a philologist, nor a geographer, nor an ethnographer; I see, I observe, I take notes and I faithfully tell what I have to say”.

Addio, terra di Toba, chi sa se ti vedrò più mai; a te devo ore indimenticabili per la lotta di sentimenti che mi suscitasti in core; non si dimenticano i palpiti di gioia ad ogni nuova scoperta, né i tremiti per la tema di un insuccesso. Nell’allontanarmi da quel lago provavo qualcuno di quei sentimenti che opprimono nel dire addio alla donna amata. Si lascia sicuri di ricordarsene sempre e di portare con sé lo struggimento di tornarle vicino. Addio o arrivederci, comunque sia, ogni cantuccio di quella terra come ogni riflessione della sua voce è vivo in voi e nella pena della separazione si trova la gioia di accorgersi quanto l’impressione provata fu forte (Modigliani 1894: 6).[1]

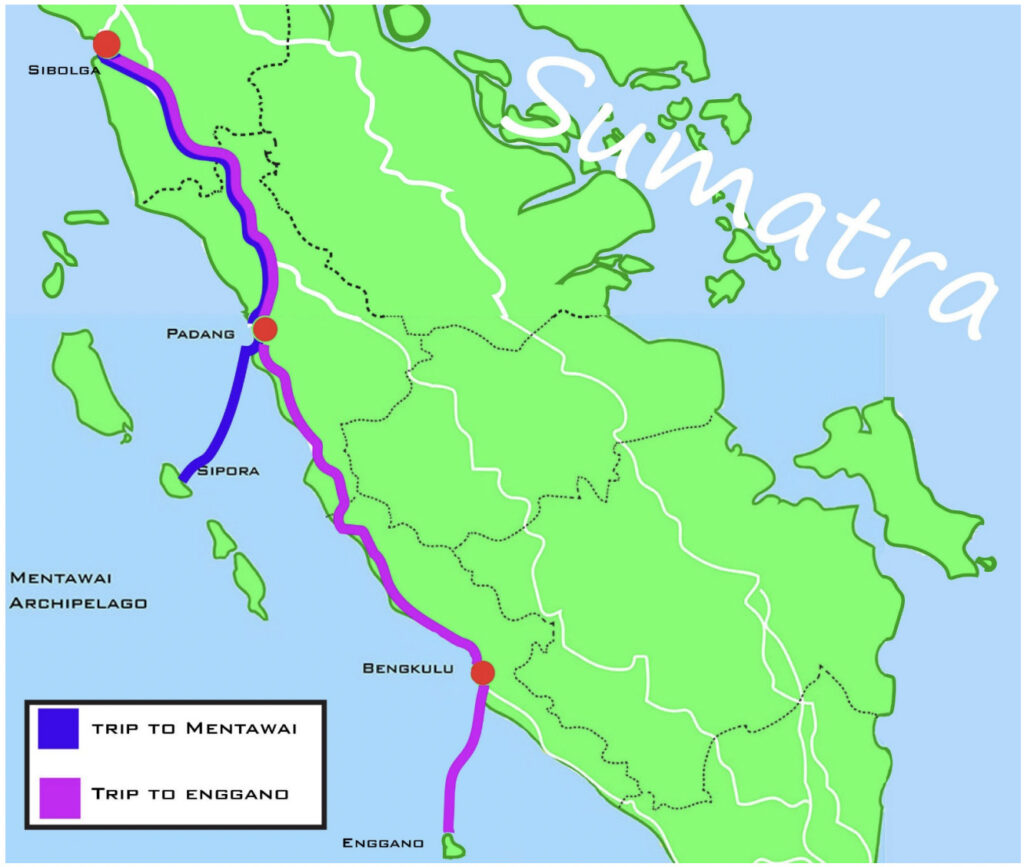

In February 1891 Modigliani received a letter from Controleur Van Dijk in Laguboti that he should leave the Batak lands – Modigliani went to the island of Enggano, for an expedition commissioned by the Batavia Geographical Society. On March 4th 1891, he left the Batak lands and sailed via Sibolga, Padang (April 16th) and Bengkulu to Enggano, which they sighted from the ship on May 3rd 1891.

Non avevo alcun progetto prestabilito; mi sovvenne che a Batavia alcuni mi avevano raccomandato come scopo di una prossima escursione l’isola di Enggano, l’isola della gente nuda, paese non ancora studiato ed interessantissimo. Decisi di recarmivi tanto per consolarmi di dover abbandonare la terra di Toba (Modigliani 1894:3).[2]

Enggano is a small island which, at Modigliani’s time, was almost completely unknown. It is located on the southern part of Sumatra’s west coast. The only thing that people knew about Enggano was, that according to legends that were widely known in Lampung, the southernmost province of Sumatra, Enggano was inhabited only by women who were said to be impregnated by the wind (Mardsen 2005: 258). Nobody, before Modigliani, had ever visited the interior of the island. After having spent almost a year in Toba and two months in Enggano (May – July 1891), a fever he could not cure led him to return to Italy at the end of 1891. After his research conducted in Enggano, he published L’isola delle donne (The Island of Women) in 1894 which represents an extraordinary description of the people of Enggano.

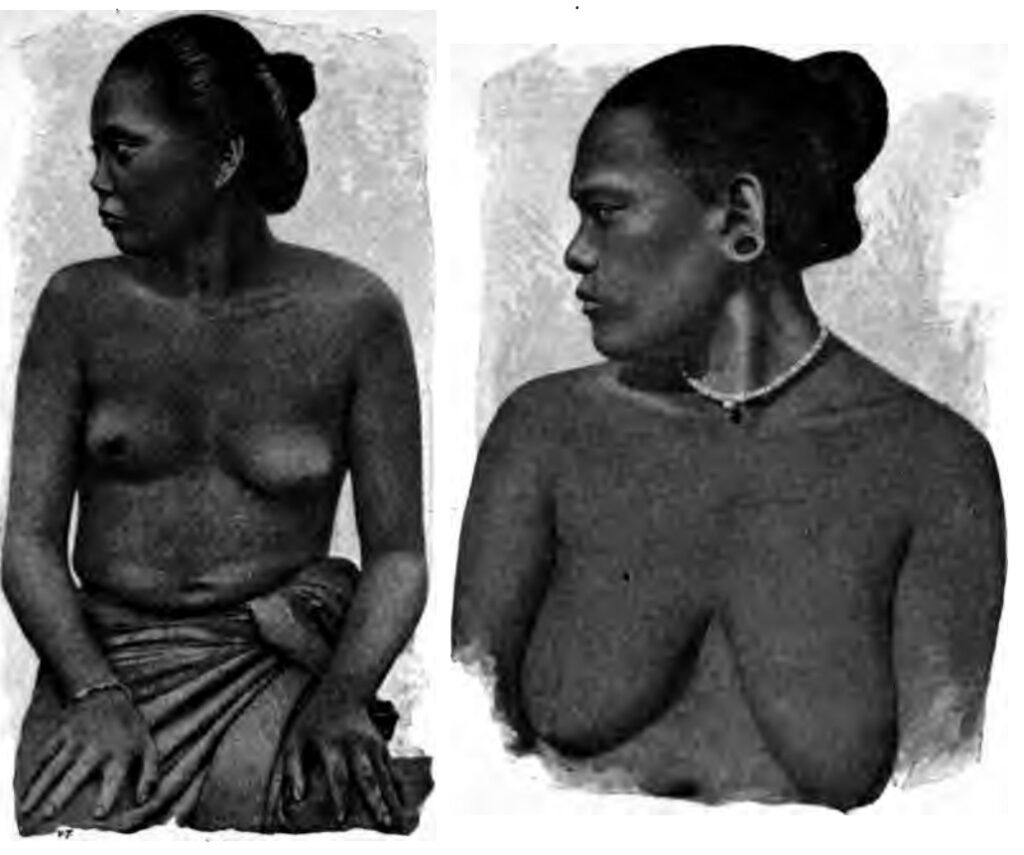

Women in Enggano (Elio Modigliani)

After almost two years in Italy, Modigliani left in September 1893 for his last expedition to explore the Mentawai archipelago, a chain of four islands: Siberut, Sipora, North Pagai, and South Pagai, plus many minor islets. The Mentawai archipelago faces the west coast of Sumatra and it is situated between the Batu Islands to the north and Enggano to the south. Modigliani chooses to travel to Mentawai to accomplish a complete study of the chain of islands that extends along the west coast of Sumatra.

Those islands were, and still are, fascinatingly diverse in terms of language, culture, and even with respect to the physical appearance of their inhabitants. Modigliani’s desire to increase the scientific knowledge of these remote islands has always been with him: everything he observed fascinated him and seemed worthy of being passed down to posterity.

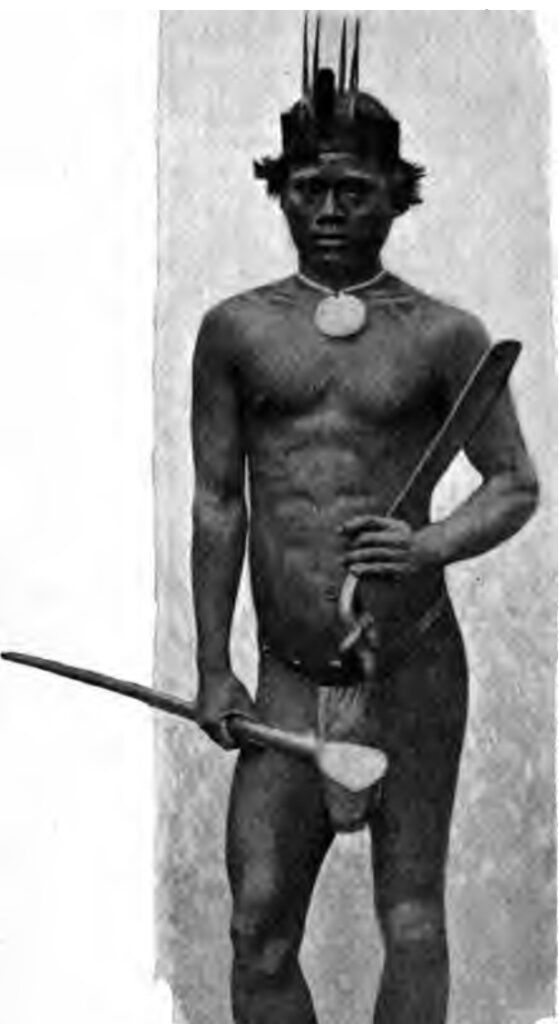

Man in Enggano (Elio Modigliani)

Modigliani never accept a refusal and had the obsession to document everything he saw. He presented himself, with the help of the medicines he had brought from Europe, as a healer. Due to his particularly audacity and shrewdness, he used every kind of strategy to achieve his goals. After all, his hypocrisy was used for a good purpose, and indeed he healed (as much as he could) everyone who asked him. In order to get gypsum masks for his anthropometric research, he went so far as to bluntly deceit his ‘patients’. In his book L’isola delle Donne he explains how he succeeded to get his first gypsum mask:

Pochi viaggiatori che io sappia si sono fino ad oggi dati a tali lavori, e per la difficoltà che s’incontra a trovare chi si voglia per il primo sottoporre a simile tormento voglio narrare come ho fatto a fare la prima. Naturalmente ci vuole un compare, e questi era uno dei miei cacciatori giavanesi. Costui a tutti raccontava la mia abilità come medico e come tra le altre cure meravigliose da me eseguite, una volta avessi reso la vista ad un cieco. Premetto che non sono un dottore in medicina! Un giorno uno si presentò a domandarmi un rimedio per guarire da una malattia ad un occhio ed io, per fargli vedere in che cosa consistesse il mio sistema di cura, chiamai il giavanese e davanti all’altro gli feci la maschera; quando vide che gliela levai di sulla faccia, senza avergli portato via la pelle né strappato un pelo non temè più nulla e di buon grado si assoggettò a tentare la prova (Modigliani 1894: 79).[3]

Modigliani also uses his medical skills to deceive the people of Enggano; on the other hand, he is sympathetic towards his patients. Modigliani often uses a comparative approach in his attempts to understand the people of Sumatra and their cultures in that he contrasts the culture of his study objects with his own culture. For instance, he does not easily dismiss the refusal of the people to give him a sample of hair as mere superstition, but he admits that in his own culture too, people are hesitant to give their own hair to someone else.

La malaria infieriva intorno a me anche tra gl’indigeni e tutti venivano a farsi curare; la mattina e la sera sembrava che la mia casa fosse una farmacia, tanta era la gente che accorreva dai vicini villaggi ed il chinino faceva miracoli. Tutti lo conoscevano ormai come rimedio sicuro e non ne avevano più paura. Approfittai anche di quella furia di venire a consultare la mia scienza medica per ottenere alcuni campioni di capelli che non volevano darmi in nessun modo. La paura a dare capelli è generale presso tutti i popoli e senza andare tanto lontano, nelle stesse nostre case si troverebbe qualcuno che si rifiuterebbe energicamente ad una simile domanda; ovunque si teme che il possessore dei capelli possa acquistare influenza sulla persona alla quale appartennero (Modigliani 1894: 231-232).[4]

He finds points in common with the people he encounters, creating broader and more intimate connections with them. Nonetheless, his first meeting with the local populations of Sipora was not a success, and neither were the following encounters, as Modigliani himself described in his first letters. The first problems that Modigliani came by were connected to Mentawai’s belief system. They believe that every object possesses a distinct spiritual essence; this includes the physical environment, plants, rocks, rivers, and animals. Spirits prefer to live in the forest. They punish those who violate taboos or otherwise act inappropriately. Nobody is allowed to cut a tree without permission from the forest authorities and from the spirits of the wood. To maintain balance and harmony among the spiritual, human, and the natural world, and to safeguard against misfortune, the Mentawai people perform various ritual offerings. Modigliani realised that this complex belief system might constitute an obstacle for him:

A si Oreina feci regali e dissi che tra qualche tempo volevo andare più in su sul fiume e stabilirmi per cercare uccelli, serpenti ecc. Accettarono, purché non sparassi fucilate nel villaggio[…] Al mattino, appena giorno, ecco arrivare il capo e il mago di Si Oreina, riportando tutti i regali che avevo fatto, dicendo che restituiscono tutto perché gli uomini, i ragazzi e le donne del villaggio vogliono scappare se io vado a stabilirmi nel villaggio o nel bosco, e ostinatamente rifiutarono tutto ciò che il giorno prima accordavano. Io dissi che quando avevo fatto un regalo non potevo riprendermelo; che se essi non lo volevano accettare, potevano buttarlo nel fiume, ma che quando io avevo fatto amicizia (toccando il cuore) con uno, non potevo ritirarla; che tornassero al villaggio e dicessero che dopo due giorni sarei tornato a portare altri regali al capo ed al mago (capivo che là era il cardine del caso) ed a tutti i ragazzi del villaggio; avrei parlato, se li persuadevo, bene, se non ci avrei pensato sopra (Modigliani 1894: 545).[5]

It seems that the critical attitude from the local population as well as the severe infection he contracted, caused this mission to be shorter than expected and eventually forced him to return early to Italy, after having stayed for a few months on the island of Sipora.

Finalmente, vinto non dalle minacce degli indigeni, ma dai disagi della vita nella foresta e dalla indescrivibile umidità nella quale avevo vissuto, dopo aver visto morir di febbre uno dei miei uomini ed il capo di Si matobe, e sentendomi ridotto in pessimo stato, decisi di lasciare la foresta (Modigliani 1898: 260).[6]

After the failure of this expedition, Modigliani has never been able to venture into those remote lands again; he spent the last years of his life writing memories of his travels.

Mentawai archipelago and Enggano (Giuseppe Ferraioli)

Modigliani’s attitude was not dictated by scientific interest only; he was genuinely obsessed. He never gave up until he had reached his goal; he would have done anything to overcome the natives’ resistance: his curiosity, like a propulsive feeling, led him to take extreme risks. He tried, to quote Geertz (1973: 13), to seek ‘in the widened sense of the term in which it encompasses very much more than talk, to converse with them, a matter a great deal more difficult, and not only with strangers, that is commonly recognized’ placing himself not in a position of strength, but on the contrary showing openly his weaknesses.

His work in the field of linguistics is impressive. Despite lacking a proper education in linguistic documentation, he produced a brief Italian-Nias dictionary in Un Viaggio a Nias (1890: 654-661) just a few months after his stay in Nias; he published a short comparative Italian-Malay-Nias-Toba-Enganese dictionary in L’Isola Delle Donne (1894: 263-281), and a small dictionary of the language spoken in Sipora (Mentawai) with many ethnographic observations and valuable notes in Materiale per lo studio dell’isola di Sipora (1898: 263-299). Written by an Italian using Italian orthography (for instance he uses decat instead of dekat), this article was considered of little scholarly value by the Dutch scholar and museum curator C.M. Pleyte. In an article published in 1898, Modigliani explains his choice and closes his defence with the simple statement: ‘I am neither a philologist, nor a geographer, nor an ethnographer; I see, I observe, I take notes and I faithfully tell what I have to say’ (Modigliani 1898: 260-262). This statement perfectly describes Modigliani’s character.

[1] Goodbye land of Toba, who knows if I will ever see you again; I owe you unforgettable hours for the struggle of feelings that you awakened in my heart; I will not forget the palpitation of joy at each new discovery, nor the tremors for the anxiety of failure. As I walked away from that lake, I felt like a man feels parting from his beloved woman. He will never forget her and bring home the longing to return to her. Farewell or goodbye, however, we say it, every corner of that land, like every reflection of its voice, is alive in you and, in the agony of separation, there is the joy of noticing how strong the impression was.

[2] I had no pre-arranged project; it came to my mind that in Batavia some people had suggested to me, as a purpose of a future expedition, the island of Enggano, the island of naked people, a land that has not yet been studied and is very interesting. I decided to go to a place so far away in order to console myself for having to leave the land of Toba.

[3] Few travellers that I know have, until now, done such work, and because of the difficulty in searching for someone who wants to be the first subject to such torment, I want to tell how I did it the first time. Naturally, a helper is needed, and he was one of my Javanese hunters. He told everyone about my ability as a doctor and, how, among other treatments, I made a marvel, once I gave the eyesight back to a blind man. I start by saying that I am not a doctor in medicine! One day one came to ask me for a remedy to heal from a disease in one eye and to show him what my system of treatment consisted of, I called the Javanese, and in front of the other men, I made him a mask; when he realized that I took it from his face, without having taken away his skin or having torn away one hair, he no longer feared anything and voluntarily subjected himself to try the test.

[4] Malaria was raging around me, even among the natives and everyone came to seek treatment; from morning until evening, it looked as if my house was a pharmacy, so many people were coming from the nearby villages and the quinine did wonders. Everyone knew it now as a safe remedy and they were no longer afraid of it. I took advantage of that frenzy and used my medical knowledge to get some samples of hair that they otherwise would refuse to give me. The fear of giving hair is common to all peoples and even in our own homes, there would be someone who would vehemently reject such a request. […] Everywhere people fear that the owner of the hair can have influence over the person to whom it belonged.

[5] At Si Oreina I gave gifts, and I said that in a while I wanted to go up the river to look for birds, snakes, etc. They accepted, under the condition that I should not shoot in the village. […] In the early morning, the head and magician of Si Oreina arrived. They returned all the gifts I gave them, saying that all men, boys and women of the village wanted to run away if I persisted in settling in the village or in the forest, and they stubbornly renounced everything that they had agreed to the day before. I said that when I give a gift I can not take it back; that if they did not want to accept it, they could throw it into the river, but when I had made friends (touching the heart) with a person, I cannot take the gift back. I told them that they should return to the village and that after two days I would come back to bring more gifts to the chief and the magician (I understood that he was the decisive person) and to all the boys of the village; I would then talk to them and try to persuade them, and if I couldn’t [persuade them], I would think about it.

[6] Finally, but not because of the threats [I received from] the natives, but from the sorrows caused by living in the forest and the dreadful dampness in which I lived, after having seen one of my men and Si Matobe’s chief die of fever, and feeling reduced to a perilous state [of health], I chose to leave the forest.

References

- Geertz C., (1973), The Interpretation of Cultures, Basic Books, New York.

- Marsden W., (2005), [1784], History of Sumatra, (Ebook Produced by Sue Asscher)

- Modigliani E., (1894), l’Isola delle Donne, Hoepli, Milano.

- Modigliani E., (1894),’Elio Modigliani alle Isole Mentawai, lettera al marchese Giacomo Doria presidente della società geografica Italiana’, in Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana,VII, pp. 543-548, Rome.

- Modigliani E., (1898), ‘Materiale per lo studio dell’isola Sipora’ in Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana, Bd. XXXV, pp. 256-299, Rome.

- Modigliani E., (1910), Il tatuaggio degli indigeni dell’isola di Sipora (Mentawei), AAE, 40, pp:45-54, Rome.

Giusy Monaco is a researcher, language teacher and translator. She has a PhD in Indonesian Studies, with a Philology specialisation, at the Università degli studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”.

She is currently teaching an online Italian language course for the University of Diponegoro, Indonesia.