Elio Modigliani, with his great courage and probably also due to his recklessness, managed to explore the southern part of Nias for more than six months.

Modigliani’s first trip was to the island of Nias, an island located off the western coast of Sumatra between 1886-1890. The destination was most likely inspired by Beccari who had conducted a number of expeditions into the Malay archipelago between 1871 and 1877 (Puccini 1999: 149-177). Beccari was inspired by Russel Wallace’s research about the Malay Archipelago between 1854 and 1862 reflecting a growing interest in Southeast Asia among Italian scholars.

When Modigliani reached Nias in April 1886, only a part of the island was under Dutch control, because the colonial forces were not able to subjugate the inhabitants of the southern part of the island. This area was famous for the custom of headhunting. In Nias, the tradition of cutting off heads was not only accepted in the war camp, but also for different kinds of important events within the community. For instance, it was common to hunt heads to honour a chief at a funeral, when a chief built a new house, when a chief’s son or other wealthy warrior married a chief’s daughter, or even to give more strength to an inviolable oath[…] In all these cases, the task of searching for victims was entrusted to volunteers who, for an agreed fee, promised to bring back the set number of heads appropriate to the occasion (Modigliani 1890: 79-89).

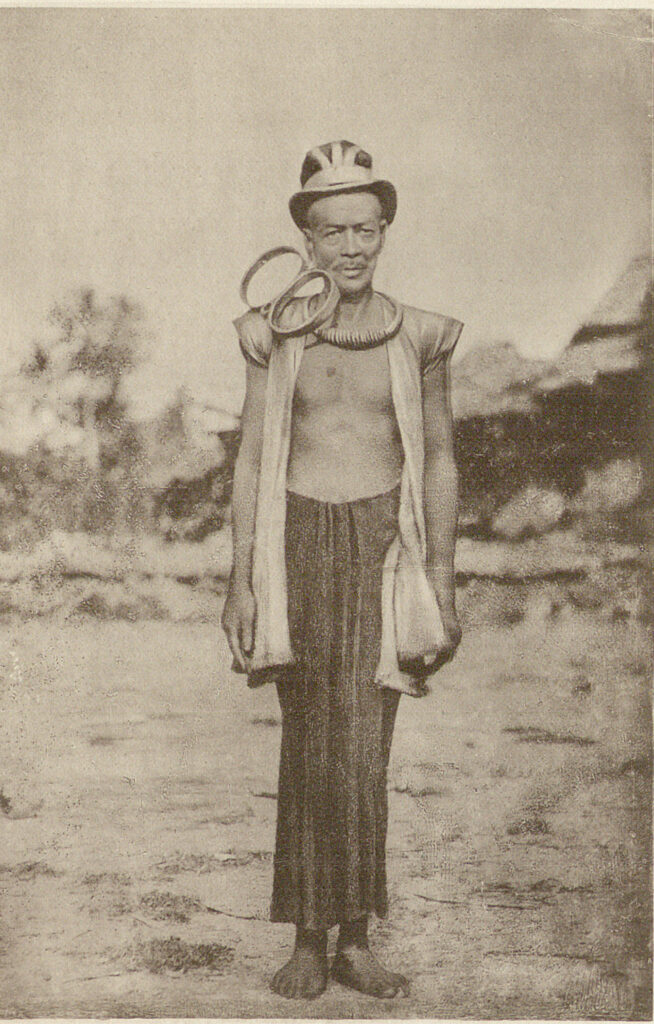

Tabeloho village chief (Un Viaggio a Nias, p.483)

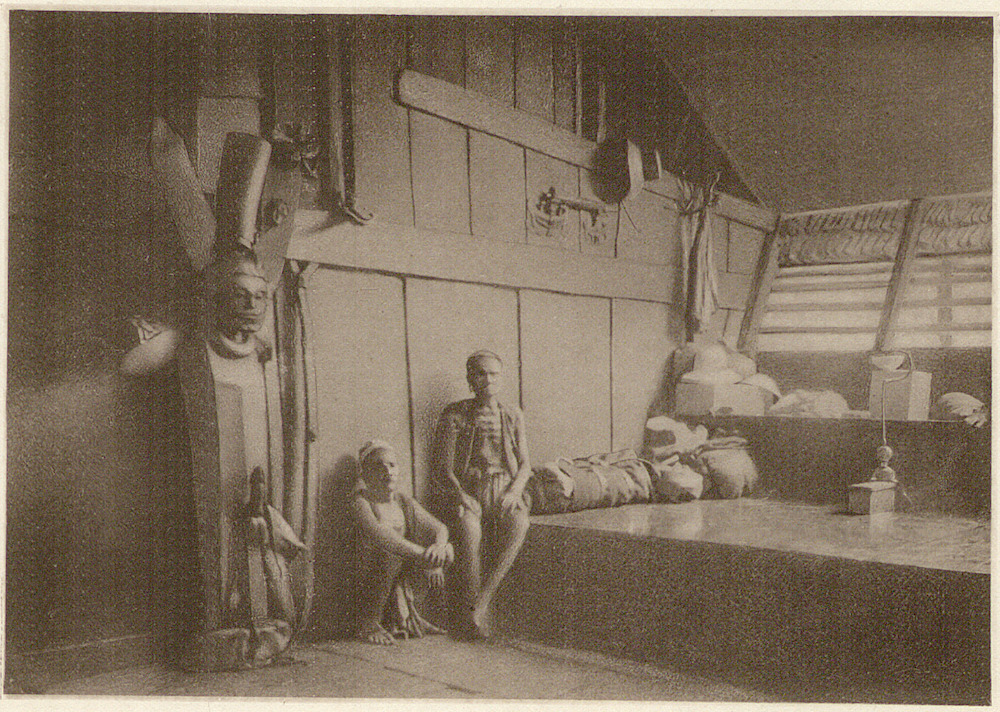

Elio Modigliani however, with his great courage and probably also due to his recklessness, managed to explore the southern part of Nias for more than six months. During his long field research in Nias, Modigliani anticipated the methods of modern anthropology, that were outlined only in the first half of the twentieth century. In his own way, Modigliani was able to collect a considerable amount of data relating to geology, climate, zoology, botany[1], and above all of that, anthropology: the social organisation of Nias, the role of women, myths and religious beliefs, music, dances, technology, language, art, architecture, et cetera. Moreover, the abilities of this man in any practical field are astonishing. He was of the first explorers to make extensive use of photography, he was an excellent carpenter and builder, a skilled diplomat known for his ability to settle disputes and a resolute and compassionate leader.

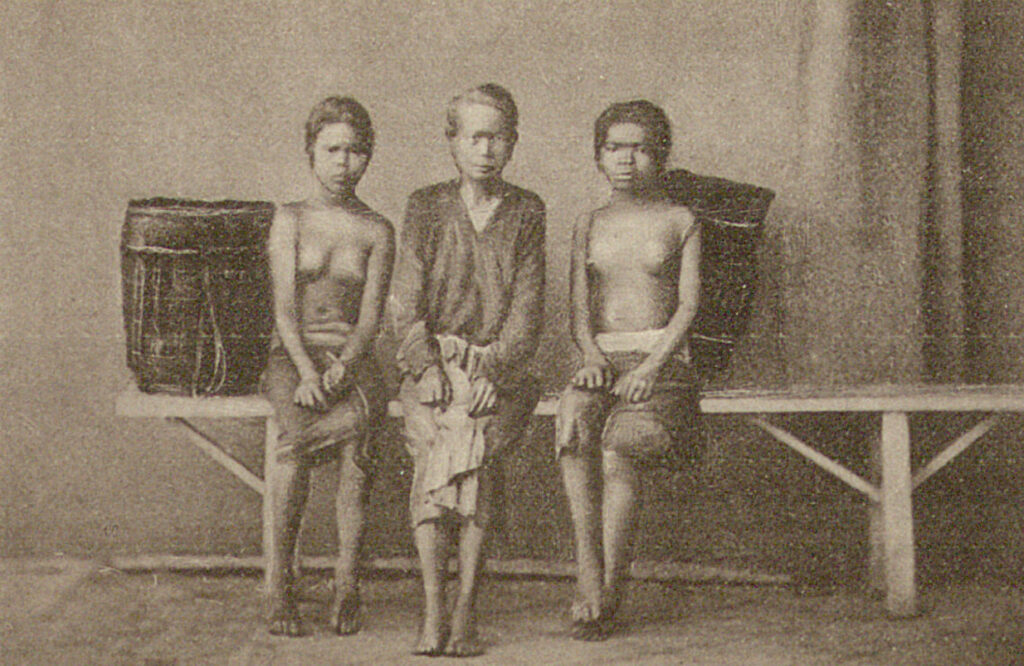

Modigliani persuaded the people, using all kinds of lies, to be photographed—even against their will. The people of Nias were afraid of the strange apparatus capable of capturing the ‘shadow of a man’ (Modigliani 1890: 563). They believed that it would take away something of a person, ‘that is inside and can not be seen’ (Modigliani 1890: 438).

Bawo Lowalani village chief (Un Viaggio a Nias, p.171)

Un giorno che mi aggiravo qua e là col mio servo nias che portava la macchina fotografica, m’imbattei vicino ad una piantagione in una donna sola. Le feci dirigere la parola da lui mentre io preparavo la macchina per fotografarla e quando fui pronto, offrendole colla maggiore riservatezza un braccialetto rosso, la condussi in un punto adatto al mio scopo e raccomandandole di stare ferma le feci il ritratto. […] Quando se ne andò era calma e tranquilla né mi sembrava per nulla spaventata da ciò che era avvenuto. Che cosa elle abbia poi raccontato quando tornò al villaggio, non so, ma è certo che a sera una frotta di uomini venne a casa fare rimostranze vivissime[…]Cercai di convincerli per le buone dando delle scuse accettabilissime[…]per persuaderli maggiormente mostrai loro alcuni ritratti che avevo meco, dicendo che quando avevo fermato quella donna, avevo preso il contorno del suo viso per far vedere al mio paese come sono le donne a Nias. Mi risposero che se avevo fatto questo, voleva dire che la donna mi piaceva e che del resto se io potevo fare quelle cose che avevo fatto loro vedere, portavo sempre via con me qualcosa della persona, una cosa che sta dentro e che non si vede. Non rimpiango davvero quest’incidente non foss’altro perché mi fornì l’occasione di raccogliere questa frase di significato profondo e certo (Modigliani 1890: 438)[2].

At the time of his visit, the Niah, as the people of Nias called themselves, were known as one of the most dangerous, and hostile people in the archipelago. To most of them, Modigliani must have appeared as a strikingly unusual and even exotic personality: not only his skin colour and his physical experience were different, but also his clothes, and the weapons he carried. Modigliani’s appearance was also quite different from that of a Dutch soldier or colonial officer for the few of them who had ever seen one. His unexpected and often extravagant or vehement behaviour must have added to his exotic appearance.

The interior of a village chief’s house (Un viaggio a Nias, p.206)

His diplomatic skills and the fact that he carried with him an adequate supply of remedies against some of the most severe tropical diseases (such as malaria) served him to obtain the title of a sorcerer (eré), and this certainly helped him to survive in those hostile territories. Upon his return to Italy in 1887, the Italian Geographical Society, which had published some of his travel reports in its Bulletin, appointed Modigliani as one of its members. The Museum of Natural History in Genoa, the National Anthropological Museum of Florence, and the Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Rome[3] welcomed with gratitude his impressive collection.

Before his departure, Modigliani has also been asked by the National Anthropological Museum to bring home human skulls to confirm some theories about physiognomy. At that time, in fact, the Italian army physician and scientist Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909) began to introduce the pseudo-science of physiognomy into the field of criminology. According to this theory, the shape of the skull would has a crucial influence on the temperament and behaviour of human beings. It is often linked to racial and sexual stereotyping since it is believed that genetic characteristics assess the character predisposition of individuals.

Woman and two girls from Tabeloho (Un viaggio a Nias,p. 544)

Even though he fulfilled this request, it seems that Modigliani was little, if at all, affected by the racist theories of his time. In his writings, he attempts to objectively describe what he sees and experiences without stigmatizing his subjects as savage or inferior. In this respect, Modigliani differs considerably from most of his contemporaries. In Un Viaggio a Nias, particularly (1890: 457-475), he describes the people he met as people who suffer, rejoice and feel emotions, without judging their relative economic backwardness as the product of an inherent biological characteristic.

[1] It is estimated that he discovered and described over eight hundred new species! (Ciruzzi 2014: 104)

[2] One day, while I was wandering around with my Nias servant carrying the camera, I came across a field with a woman working there. I made my servant speak to her while I was preparing the camera to take a picture of her and when I was ready, I slipped a red bracelet into her hand [as a gift], I took her to a location suitable for my purpose and advised her to stand still […]. When she left, she seemed calm and relaxed, and there was no indication that she might have been afraid of what had happened. What she said when she returned to the village I do not know, but in the evening a group of men came to my house to speak strongly to me[…]I tried to convince them for good by giving excuses that I hoped they would accept. […] In order to persuade them even more I showed them some portraits I had with me, saying that when I talked to that woman, I took an impression of her face to show my countrymen what the women of Nias look like. They [also] told me that if I had done this, it meant that I liked the woman and that if I could do those things that I had shown them [taking pictures], I always took something of the person with me, something that is inside [the person] and cannot be seen. I really do not regret this incident because it gave me the opportunity to gather this expression of deep and particular meaning.

[3] The museum was founded in 1869 by Mentegazza and contains over four million specimens from all over the world, with the aim to document the many aspects and manifestations of diversity, biological and cultural, of the species homo sapiens. Mentegazza was a medical doctor, but soon turned to study humans and held the first chair of Anthropology in Italy and forged a new science that he defined as the «Natural History of Humans» (Cecchi et al. 2014: XV). Moreover, Mantegazza together with Luigi Pigorini were the first in pushing Italy to collect and to document ethnographic and anthropological objects (Puccini 1999: 17-41).

References:

Modigliani E., (1886), in Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana II-Volume XI:

- ‘Escursione nell’isola Nias (a Ovest di Sumatra)-Lettera di E. Modigliani al prof Arturo Issel’, pp.782-787, Rome;

- ‘Escursione nell’isola di Nias- Lettera di E. Modigliani al prof Arturo Issel’, pp.854-862, Rome. Modigliani E., (1886), in Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana II-Volume XII:

- ‘il Cota Ragia e l’Isola di Nias-Lettera di E. Modigliani al prof Arturo Issel’, pp.24-35 Rome.

- ‘l’Isola di Nias (note geografiche del socio Elio Modigliani con una carta)’pp. 595-717, Rome. Modigliani E., (1889), ‘Da un’opera sull’isola di Nias del socio corrispondente dottor E. Modigliani’ in Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana II pp.764-772, Rome.

Modigliani E., (1890a), Un viaggio a Nías di Elio Modigliani: Illustrato da 195 incisioni, 26 tavole tirate a parte, e 4 carte geografiche., Fratelli Treves, Milan.

Giusy Monaco is a researcher, language teacher and translator. She has a PhD in Indonesian Studies, with a Philology specialisation, at the Università degli studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”.

She is currently teaching an online Italian language course for the University of Diponegoro, Indonesia.