In the autumn of 1890, Elio Modigliani left for his second expedition to the Indonesian archipelago, this time heading for the still independent Batak Lands in the centre of Sumatra.

Da che Catullo ha cantato il lago di Garda, ed una intera scuola di poeti scozzesi ha vantato le bellezze di quelli di Scozia, tutti i laghi hanno avuto il loro poeta, e certo verrà il giorno che alcuno dirà in versi di quello di Toba, e se lo merita. Erano le prime ore di un’umida mattinata, quando quel silenzioso e nebbioso bacino d’acqua vastissimo si aprì ai miei occhi per la prima volta: mi fece un’impressione di tristezza e di solitudine strana. Erano degli anni che io facevo l’amore con la terra di Toba; avevo studiato il suo lago su tutte le lettere dei missionari che lo descrivevano come una rivelazione di paradiso, ed io restavo muto (Modigliani 1892: 59-60).[1]

Elio Modigliani was accompanied by a number of Javanese assistants, who were able to communicate in Malay. One of his assistants, Sigutala, was a Toba Batak and therefore he could speak the local language. To Modigliani, it was important to have at least one person fluent in Toba Batak because only a few Batak mastered the Malay language. Modigliani was determined not only to penetrate the independent Land of Toba but also to start a good relationship with local chiefs in order to gather as much information as possible.

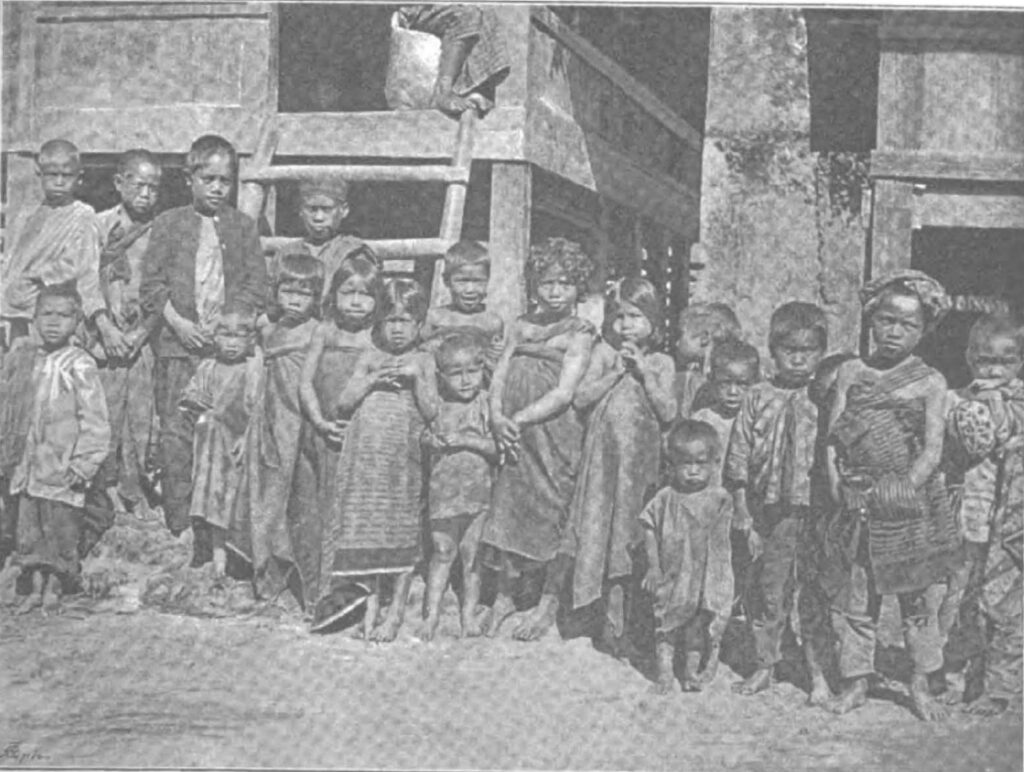

A group of Toba Batak kids (Fra i Batacchi indipendenti: viaggio)

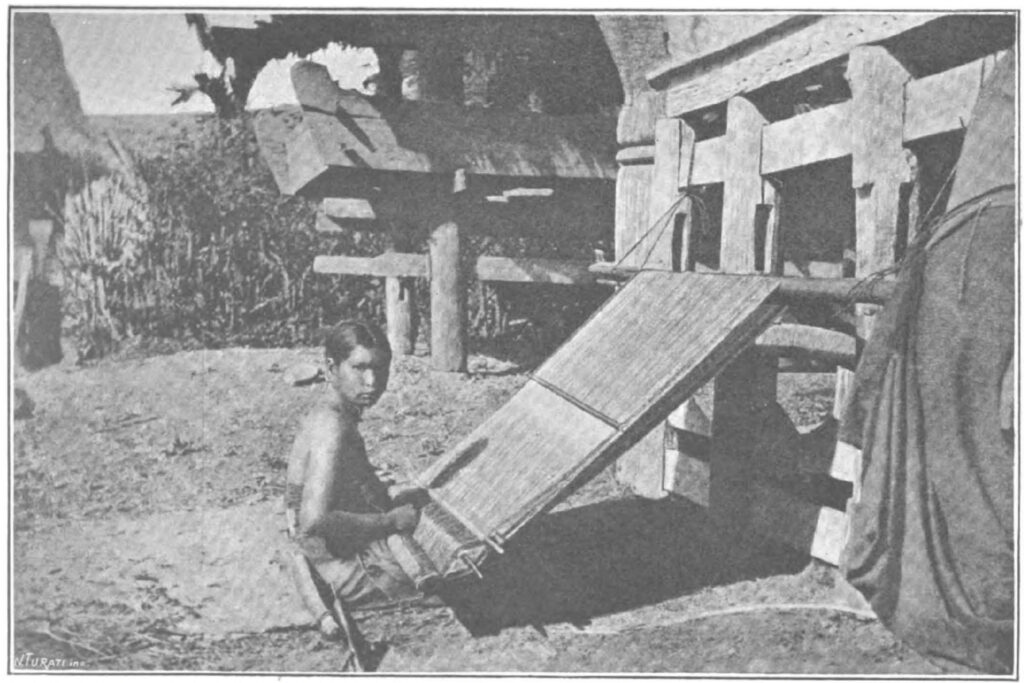

During the expedition, Modigliani documented the natural and cultural environment, and the people in numerous drawings and photographic images, together with a significant number of items of the material culture as well as botanical and zoological. Modigliani was one of the first explorers who had studied photography and was hence able to take excellent photographs, prepare them into tin boxes and send them to Italy.

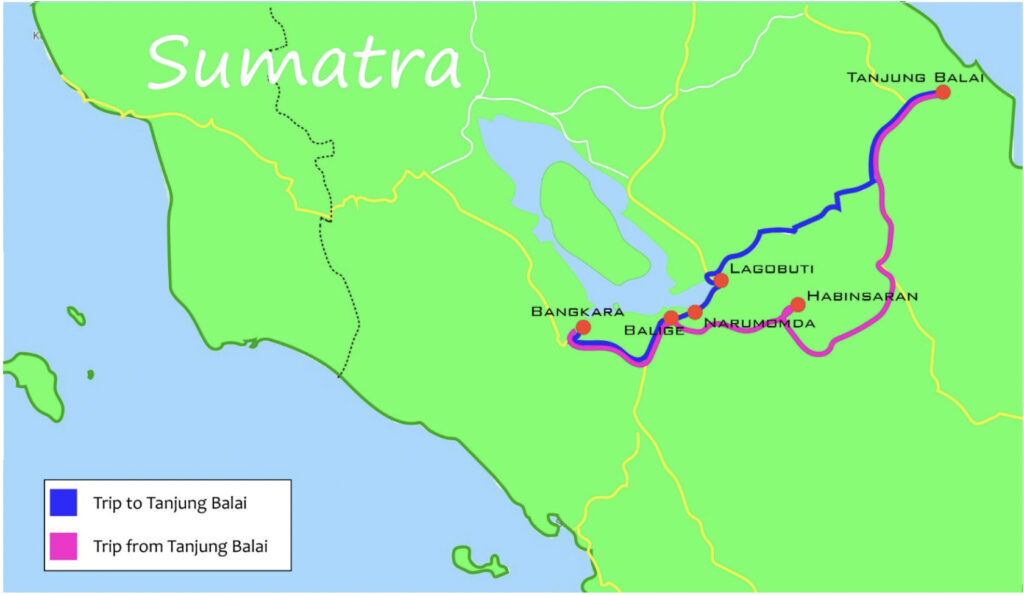

He travelled around Lake Toba, which is the largest volcanic lake in the world with a surface area of 1,130 km2. In the midst of Lake Toba rests the beautiful island of Samosir covering over 630 km2 – approximately the size of Singapore. Samosir was at that time one of the most isolated, yet densely populated parts of Sumatra. Nonetheless, Modigliani succeeded in mapping Lake Toba and accurately measured its length and width (100x30km), he made meteorological observations and verified the proposed theory of the volcanic origin of Samosir Island.

Lake Toba (Giusy Monaco)

During the course of the 19th century, the Batak area had largely retained its independence except for the southern parts. Mandailing was already subjected to Dutch control by 1843, and Silindung and some parts of Toba were conquered during the Toba War of 1878-1879 after the German missionary Nommensen had called the Dutch army to suppress a resistance movement by King Singamangaraja XII. The rest of the Toba Batak region was only colonised between 1904 and 1907. The German Rhenish Missionary Society (Rheinische Missions-Gesellschaft) with Ludwig Ingwer Nommensen as its most prominent member, settled in the Silindung valley around 1861, and during the Toba Wars Nommensen assisted the Dutch army as a guide. Yet, Bangkara and the surrounding area were not immediately subjected to Dutch control and remained largely independent, but in a state without any strong authority to guarantee the safety of a traveller. The only Batak chief who had considerable influence outside his own district was Singamangaraja XII of Bangkara, which the Dutch had ousted from his village a few years before Modigliani arrived.

Modigliani began his journey in Sibolga on 8 October 1890 on the west coast. From here he continued to Silindung, and then further to Balige, where he arrived on 16 October and stayed for one month. From Balige he went to Laguboti. This journey was relatively easy as this part was already under Dutch control with a Controleur resident in Laguboti. From Laguboti he travelled further to Sabulan and Bangkara which had just been pacified by the Dutch. He chose Bangkara because he wanted that the Singamangaraja to hear of his arrival, and also because of its vicinity to the yet independent Batak Lands. He realised how important it was to maintain good relationships with the local people who still vehemently hated the Dutch, and consequently all halak na sibontar mata (people with light-coloured eyes) and who were still loyal to Singamangaraja.

A woman weaving (Fra i Batacchi indipendenti: viaggio)

In Bangkara Modigliani unmistakably declares that he is not a Dutchman but that his sovereign was the king of Rome. Many Indonesian Muslim states have had centuries of diplomatic and military relations with Ottoman Turkey. Since the sixteenth century, the title Raja Rum referred to the Ottoman Sultan. Modigliani was hence perceived as the emissary of the legendary figure of Raja Rum. Soon the rumour spread that the Ottoman Sultan had sent an emissary to the Batak people to help them in their struggle against the Dutch. Modigliani explained this misunderstanding, the method used to overcome it and also that he decided to benefit from it (in several situations) in his travel reports:

Mille domande politiche mi furono fatte: vollero sapere ‘come stesse il mio cuore a riguardo del Singamangaraja’ che cosa pensassi dell’Olanda, se volessi proprio stare in pace e mille altre. Risposi che il mio Ragia è potentissimo e che mi ha mandato a Toba perché vuole vedere come sono vestiti i Toba e quali oggetti usano. ‘E chi è il tuo Ragia?’. ‘È il Ragia Roma’ – risposi, tanto per dire qualcosa. Ne seguì un gran discorrere tra di loro: finalmente uno di essi mi domandò come mai, poichè essi avevano varie volte mandato cavalli e bufali al Ragia Rom, egli non avesse mai ringraziato ne contraccambiato. ‘In quale pasticcio mi sono cacciato e chi è questo Ragia Rom del quale si parla?’Pensai tra me.’ ‘Il Ragia Rom – dissi loro – non ha mai ricevuto i vostri doni; voi forse li avete mandati ad Aceh, e il Ragia Aceh se li è tenuti’. Ciò li convinse assai[…]A me il Ragia Rom fa molto comodo (Modigliani 1892: 75-76).[2]

After his visit to Bangkara, Modigliani continued his trip toward the northwest side of Lake Toba to see its outlet, the Asahan river, and also to view the famous waterfalls by which this river descends. Arriving in Laguboti, Modigliani requested an official permit to enter the independent Batak Lands. However, his request was, most likely for safety reasons, denied.

Map of Modigliani’s journey into the Batak Lands (Giuseppe Ferraioli)

Initially, Modigliani believed that the denial to grant him a travel permit was based on a misunderstanding since the authorities in Batavia had authorised his trip explicitly stating that he was free to travel anywhere he wanted. When he sent a letter to some friends in Batavia asking them to clarify the issue with the Governor General of the Netherland Indies, the reply was an unmistakable denial of his initial request. He nevertheless decided to venture into the interior, which was outside of Dutch control. Yet, every attempt to convince a village chief to become his guide, was in vain, as they feared the punishment of the Controleur. The constant denials apparently only increased Modigliani’s desire to travel ‘che divenne una febbre, una frenesia; passavo le notti senza chiuder occhio, organizzando piani, combinando progetti, e sempre mi vedevo di mezzo il Controleur, che solo stendendo un dito distruggeva ciò che io aveva con tanta pena fabbricato‘ (Modigliani 1892: 83).

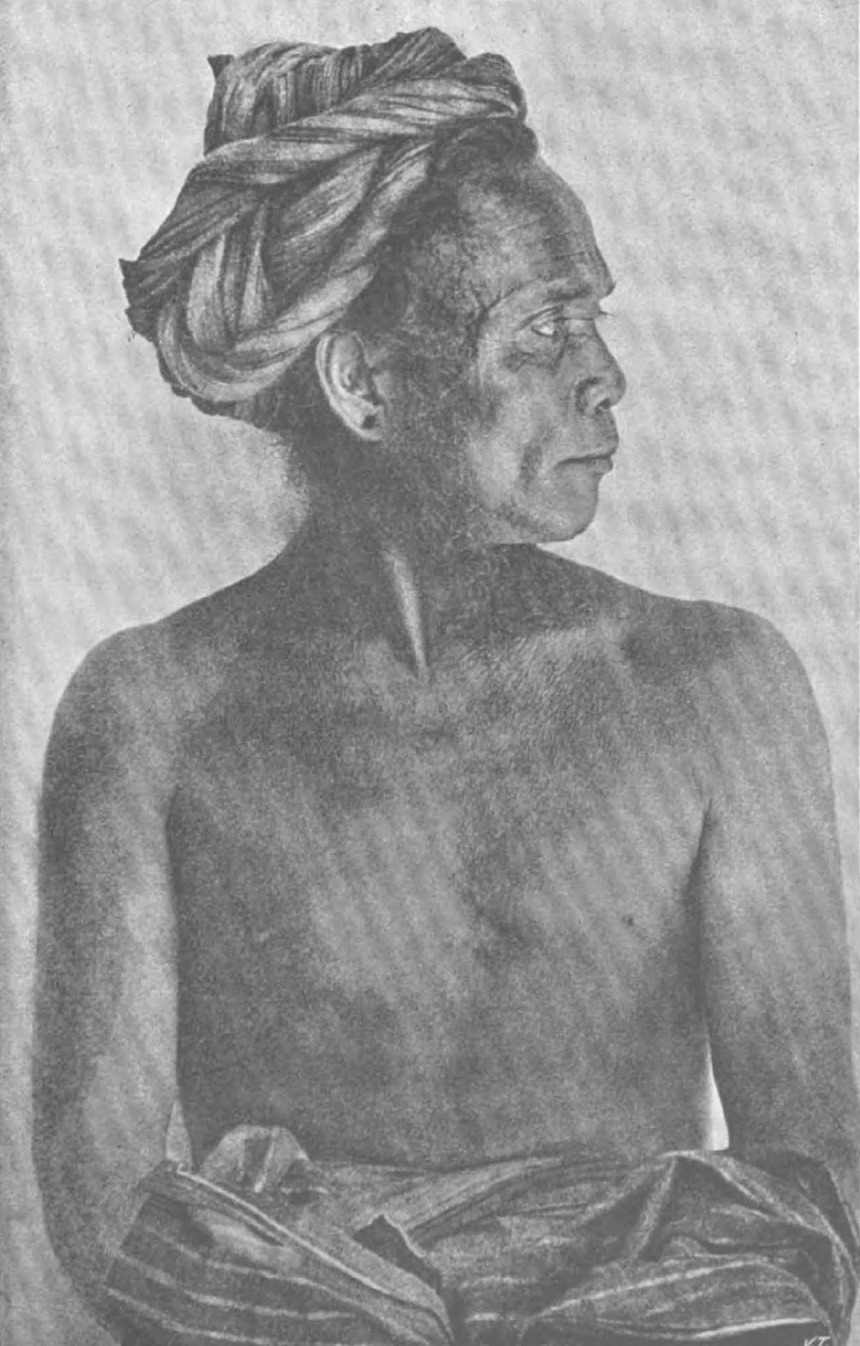

After all those unfruitful attempts, Modigliani finally decided to ask the help of Guru Somalaing Pardede. The well-known magician-healer (called guru or datu) was born in the 1840ies in the vicinity of Balige—the capital of what is now the Toba Samosir Regency. He was one of the advisors of Singamangaraja until 1886, and together they fought against the Dutch in 1878 and 1883. The late 19th century was a period of radical political, social and religious transformation. Until the late 1860ies, the Toba people knew about western culture only through occasional contact with the coastal area which they sometimes visited for the purpose of trade, or with the occasional missionaries that visited the interior, but these contacts had no profound impact. Somalaing’s perception of Modigliani as an emissary of the Raja Rum, combined with Modigliani’s unconventional ways and attitudes, assisted the Batak to question the legitimacy of the Dutch rule. Modigliani was surely aware of this misunderstanding and with an ironical and in some way comical honesty he revealed that he decided to lie in order to get Guru Somalaing as a guide for his journey into the independent Batak lands. Eventually, Modigliani started to consider him a real friend:

Non avevo scelta; conveniva mentire per poter viaggiare. Mentii.[…]Costui fu per me un vero amico non una guida; mi protesse del suo corpo quando stavano per tirarci contro, mi consigliò sempre, garantì di me in ogni frangente e certo gli devo la vita o la libertà (Modigliani 1892: 85-86).[3]

Modigliani was skilled, lucky and shrewd enough to overcome the obstacles, impediments and even hostilities he faced. The journey to the Sampuran Si Arimo waterfall, for instance, was arduous, and the local people were frightened by the belief that the waterfall was the dwellings of a powerful sombaon, a spiritual being. Once he reached the village Tanga, where the coveted waterfall is located, Modigliani took again the advantage of the misunderstanding that he was the emissary of Raja Rum.

Guru Somalaing Pardede (Fra i Batacchi indipendenti: viaggio)

With the help of Guru Somalaing, and due to his courage and also a big amount of luck, Modigliani and Somalaing were able to identify the Asahan river with its mighty waterfall Sampuran Si Arimo as the only outlet of Lake Toba. When we read Modigliani’s record about the moment of his first sight at that waterfall, we notice how deep his understanding of the Batak’s culture, and how he felt to be part of this group:

Non ricordo di aver mai provato un’emozione pari a quella che mi dominava, mentre fotografavo il Sapuran si Arimo; che è questo il nome della cascata. Altri la vedrà, ma difficilmente per gli altri si svolgerà la scena di vita intima batacca che si chiuse per me col il permesso di vedere quel grandioso spettacolo.

Mi ero immedesimato coi batacchi, e quasi quasi aspettavo da un momento all’altro che il sombaon (i.e. esseri spirituali come antenati particolarmente venerati o manifestazioni di una divinità), offeso dal mio ardire di fotografare la sua dimora, uscisse dai neri massi, nei quali si dice egli abiti, e mi punisse. (Modigliani 1891: 376).[4]

[1] Since Catullus praised the Lake of Garda, and an entire school of Scottish poets claimed the beauties of the lochs of Scotland, each lake has had its own poet, and certainly, the day will come when a poet will praise the beauty of Lake Toba, and it truly deserves it. It was in the first hour of a humid morning when that silent and misty enormous water basin for the first time revealed itself to my eyes: it provoked inside me an impression of sadness and rare loneliness. Years have passed since I started to love the lands of Toba; I learned about her lake in the letters of the missionaries who call it a revelation of paradise, and it made me speechless.

[2] They asked me thousand political questions: they wanted to know “how my heart felt about the Singamangaraja”; what I thought about the Netherlands if I came with peaceful intentions and thousand more questions. I replied that my Raja is mighty and that he sent me to Toba because he wants to see how the Toba dress and what kind of tools they use. ‘And who is your Raja?’ ‘He is the Raja Roma’ I answered, merely to say something. A vivid discussion erupted among them: finally, one of them asked me how this was possible since they had several times sent horses and buffaloes to the Raja Rom, but he never thanked them or sent anything back.’What kind of mess have I gotten myself into and who is this Raja Rom that they are talking about?’ I thought to myself. ‘Raja Rom’, I told them, ‘never received your gifts; you might have sent them to Aceh, and the Raja Aceh kept them. This answer convinced them […]. To me, their belief in the Raja Rom was very convenient.

[3] I had no choice; it was more convenient to lie in order to travel. I lied […] He became a true friend to me, not a guide; he shielded me with his body when they were about to attack us, he had always advised me, he became my guarantor in every situation, and I certainly owe him my life or my freedom.

[4] I do not remember ever having experienced an emotion equal to that which dominated me while I was photographing Sampuran si Arimo; which is the name of the waterfall. Other people will see it, but it will be hard for others to feel what I felt as it revealed itself when I had the chance to watch that magnificent spectacle. I had identified myself with the Batak, and I somehow was waiting that, at some point, the sombaon (i.e. Spiritual beings such as particularly revered ancestors or manifestations of a deity), offended by my audacity to photograph his dwelling place, would come out of the black rocks, in which he is said to live, to punish me.

References:

- Modigliani, E., (1891), in Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana, IV:

– ‘Elio Modigliani fra I Batacchi Indipendenti lettera al presidente della società geografica Italiana’, pp.367-384, Rome.

– ‘Tra il Lago Toba e Bandar Pulo lettera del socio corrispondente dottor E.Modigliani a suo cugino Arturo Issel (con una carta originale del viaggio)’, pp.588-606, Rome.

– ‘Tra il Lago Toba e Bandar Pulo lettera del socio corrispondente dottor E.Modigliani’, pp. 633-664, Rome. - Modigliani E., (1892), Fra i Batacchi indipendenti: viaggio, (Vol. 25), Società Geografica Italiana, Rome.

Giusy Monaco is a researcher, language teacher and translator. She has a PhD in Indonesian Studies, with a Philology specialisation, at the Università degli studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”.

She is currently teaching an online Italian language course for the University of Diponegoro, Indonesia.